Book 2 of 10 on my #NBAward Poetry Longlist Reading Journey

Life on Earth by Dorianne Laux starts off with a bang with a poem about The Big Bang Theory. “In Any Event” posits that humanity is infinitely expansive like the universe. Laux believes in humanity’s potential so deeply it’s contagious. I was energized by this confident line at end of the poem. Sticking her neck out for humanity, she says “and I praise us now, / in advance.

“There is something / more to come, our hearts / a gold mine / not yet plumbed, / an uncharted sea.

[…] we can find out way / into anything.”

“In Any Event” p 3

“In Any Event” kicks off the collection’s theme of praise (for life on earth) and a complex motif of gold-mining the heart, two things I annotated until the very last page. Of note, this first poem stands alone, cut off from the main body of poetry by Laux’s dedication.

“In Any Event” has some gently satisfying sound patterns. The closing sounds of the first stanza (“since and hence”) echo in the poem’s final word “advance.”

54 Soft and Sharp Poems

In Life on Earth, Dorianne Laux mines her life experiences for gems, both beautiful and flawed. Her inspiration clearly draws from family, the natural world, seasons of life, historical events, other artists, and movies. I think the poems read like answers to these stimuli, and Laux makes me feel like life’s moments are living things to converse with.

My Favorite Poems

Poems That Frustrated Me

- Tulip Poplar

- Smash Shack

- Mugged by Poetry

- East Meets West

Why I Struggled With “Tulip Poplar,” a Poem About Lynching

“Tulip Poplar,” poem 21 of 54, arrives in the middle of the collection. This poem is about life taking life on earth: white people lynching Black people. The poem did not land, and I needed it to land because of the subject matter.

Laux approaches lynching through ekphrasis, honoring Billie Holiday’s monumental recording of the song “Strange Fruit.” Laux specifically references the lines “Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze / Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.“1

Laux’s poem is 32 lines long. The first 27 lines are pastoral praise for the poplar tree. She goes into great detail about the tree’s seasonal changes, the birds sheltering in it, and even the wood’s economic utility. I think this section is in conversation with the lyric “Pastoral scene of the gallant south” from Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” and that Laux’s bird details might (in some disturbing way) be in conversation with the crows in Holiday’s song.

Then the pastoral section ends with a shocking volta:

“and died. Don’t ask me why” / we would hang bodies from such beauty,

When the poem gets here, I just wanted to toss my book. What went through my head:

- What do you mean I can’t ask you about this?

- Why is the poem’s door so abruptly and rudely shut in my face?

- Is this a cop out at the critical moment?

- Wait, what am I not getting? Am I misreading?

There’s No Leap Shared

I care that Laux brought lynching into her collection. It’s one of the few moments that she reckons with race explicitly in the book. In a book by a white American woman about life on earth in the United States at least one poem on this subject feels truly necessary. But I don’t understand the point of this poem.

To be clear, it is ok with me if Laux doesn’t have an answer to a question about hate crimes. It is ok with me if she has nothing to say beyond a condemnation of lynching. But it is icky to me that she withdraws at the critical moment and says nothing.

I especially care about the silence she chose when writing “Don’t ask me why.” Laux is a white woman like me. She’s my mom’s age. So far, I’ve been looking up to her and marveling at the wisdom in this collection. In this poem, I thought she was taking me with her on a journey that honors the protest art of a Black woman — how Billie Holiday used her voice, platform, and career at no small risk to protest lynching. I was aching for Laux to do something similar with her voice and career and take me with her. But there is no protest for me join in as a reader. I’m just suddenly turned away, and I don’t feel like I’ve participated in something that honors Holiday’s song.

“Tulip Poplar” ends like this

“and died. Don’t ask me why

we would hang bodies from such beauty,

sap wood and heart wood. We live

with its dark history, it gives us its darkest,

most bitter honey.

After being suddenly cut off from Laux’s insight in this way, I really rankled against the last lines of the poem, which describe the tree’s “darkest, most bitter honey.” This imagery is a riff on the haunting final lyrics of Holiday’s song:

“For the sun to rot, for the trees to drop

Here is a strange and bitter crop”

Last thing, Laux doesn’t even say Black in her poem.

Closing Thoughts

Laux’s collection is one that I will take what I need and leave what I don’t. There is a lot in this collection that I will enrich my life with. I loved the poems about her mother. But I’m going leave things behind, like the poem “Tulip Poplar,” and I am not going to turn to Laux for art that surgically explores the ugliness of whiteness and how to attempt repair. I’ll primarily return to Black women’s art for those lessons and to the only two white women whose work I’ve really admired on this subject recently: Maud Newton’s Ancestor Trouble and Drew Gilpin Faust’s Necessary Trouble.

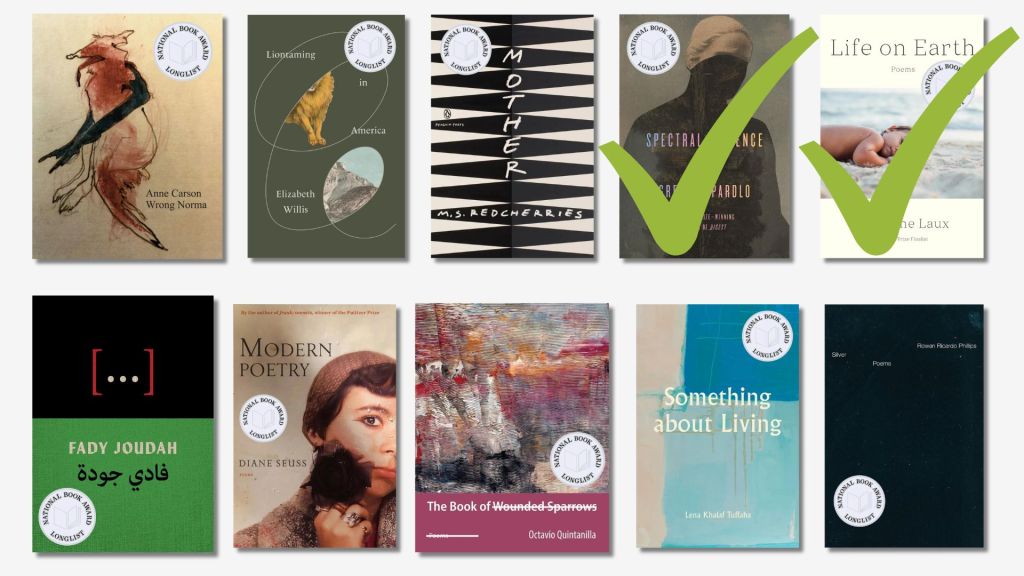

What’s Next

I’m continuing my National Book Award Poetry Longlist reading with The Book of Wounded Sparrows by Octavio Quintanilla.

- This is spelled out in the Acknowledgments section on page 92. ↩︎